Have the rise of online Social Media advocacy and the recent Occupy Wall Street 99% Movement had an impact on traditional Community-Based Organizations (CBOs)? How are community-based organizations (CBOs) adapting to new organizing challenges in the 21st Century? What role are CBOs playing in developing new coalition-driven and collaborative models of organizing, advocacy and activism? Is there a reflexive relationship at play where established CBOs are working effectively with new online Social Media organizing and advocacy techniques, linking up with unfunded, decentralized activist networks such as the Occupy Movement, in effect altering the landscape of the modern progressive Left?

This article will make the case that challenging, yet promising opportunities lie in just this reflexive relationship. Long stereotyped as comprising a fractured whole, less unified than their conservative counterparts, are established CBOs and unfunded activist networks forming new collaborative models, making more with fewer overall resources and advancing new strategies capable of galvanizing the Left into a more cohesive movement, unifying a collective local to global focus?

Literature Review

This study provides respectful response to an article by Joseph Heathcott (Heathcott: 2005) where Heathcott is largely complementary of NPA (formerly NPA/NTIC—the National Training and Information Center) yet positions the organization as part of a broader social justice community organizing movement that has failed to achieve: “broad-based change.” I argue that, conversely, organizations like NPA are doing some of the most promising work that, by targeting banks and corporations that are global in scope, is in fact “broad-based” and “transformative,” with global implications and potential impact. I also make use of definitions of “transformative” versus “power-based” CBOs as identified by Kristina Smock (Smock: 2004). Further, I gain much insight from Rinku Sen, author of Stir It Up: Lessons in Community Organizing and Advocacy. Sen highlights the need for a balance between transformative exercises of popular and political education and power-based efforts seeking tangible policy change through issue and campaign-based organizing strategies (Sen: 2003).

Additionally, this article involves a response to the writings of Richard A. Cloward and Frances Fox Piven, primarily “Disruptive Dissensus: People and Power in the Industrial Age.” Cloward and Fox Piven argue that moments of “disruptive dissensus” (such as the Womens’ Suffrage Movement, the Civil Rights Movement and the recent Occupy Movement) have brought about real transformative change in the U.S.while, conversely, “poor people’s organizations” have accomplished very little. This article will make the competing argument that, while moments of disruptive dissensus do in fact create the climate for broader social and economic change, CBOs and their allies have historically been the entities that have implemented tangible structural change. These debates will be juxtaposed aside literature that has emerged focusing on CBO organizing, the Occupy Movement, online Social Media advocacy and Social Movements Theory.

Community-Based Organizing Literature Review

Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals provides foundation in early power-based organizing ideology and technique, although many next-generation organizers have criticized an over-emphasis on the “Alinsky model,” citing less white male-centered organizing efforts both pre and post-Alinsky that have told a story more inclusive of the contributions of women and people of color. Questioned on similar grounds, yet also informative are Blessed be the Fighters: Reflections on Organizing and Dynamics of Organizing: Building Power by Developing the Human Spirit, by the late co-founder of NPA, Shel Trapp.

In Community Organizing: A Brief Introduction, author Mike Miller, founder and E.D. of the ORGANIZE Training Center, states that “Alinsky’s approach has since been revised, modified, expanded, and elaborated to meet new circumstances.” Yet Miller’s work is nonetheless a useful primer on the basics of CBO organizing (Miller: Introduction). Miller is also the author of A Community Organizers Tale. Organizing for Social Change: A Manual for Activist in the 1990’s by Kim Bobo, Jackie Kendall and Steve Max is a further useful primer. Industrial Areas Foundation longtime leader Edward. T. Chamber’s Roots for Radicals: Organizing for Power, Action and Justice also provides a next generation look at the classic Alinsky model.

For post-Alinsky organizing, the identity politics of race, class and gender in organizing, in popular and political education and transformative organizing ideology and strategy , the aforementioned works by Sen and Smock are insightful. Smock’s book also focuses on women-centered models of community organizing and classic civic participation models of grassroots engagement. Beyond the Politics of Place: New Directions in Community Organizing by Gary Delgado, early architect of the transformative model of organizing and founder of The Applied Research Center (ARC) and the Center for Third World Organizing (CTWO)—each founded in Oakland, CA--also provides alternative critical counterpoint to the classic Chicago-based Alinsky approach. Roots of Justice: Stories of Organizing in Communities of Color by Larry Solomon is also useful along these lines.

As this article illustrates, in modern-day organizing, clear delineations between power-based and transformative organizing are no longer fully relevant. Power-based organizations are adopting methods of political and popular education, class, race, gender and LGBTQ analysis. Transformative organizations are likewise recognizing the need to engage leadership in structured campaign efforts with clear victories in mind that build a sustainable leadership base.

We Make Change: Community Organizers Talk About What They Do—and Why by Kristin Layng Szakos and Joe Szakos tells the story of organizing through organizers engaged in the work. Jamie Court’s The Progressive’s Guide to Raising Hell: How to Win Grassroots Campaigns, Pass Ballot Box Laws, and Get the Change We Voted For provides another hands-on manual. Eric Mann’s Playbook for Progressives: 16 Qualities of the Successful Organizer, reveals that a diversity of personalities must be brought to the table to comprise an inclusive field of organizing. Mann rightly states: “Radical organizing grows in times of despair” and makes an impassioned plea for new transformative approaches (Mann: 192).

James DeFilippis, Robert Fisher and Eric Shragge’s Contesting Community: The Limits and Potential of Local Organizing also speaks to the challenges and importance of community as space to organize and form collective identity in the face of neo-liberal, globalizing markets in the “contemporary political economy.” Randy Stoecker profiles a beneficial case study in Defending Community: The Struggle for Alternative Redevelopment in Cedar-Riverside. William Julius Williams and Richard P. Taub, in There Goes The Neighborhood: Racial, Ethnic, and Class Tensions in Four Chicago Neighborhoods and Their Meaning for America, speak to historic divisions within communities that often impede community mobilization.

From the Ground Up: Grassroots Organizations Making Social Change, by Carol Chetkovich and Frances Kunreuther, provides a framework for change cognizant of social movements theory. The work’s strongest offering for purposes here is its definitions of collaboration, including “political coalitions,” “complementary alliances,” “service partnerships and issue networks” and “joint production of legal advocacy” (Chetkovich, Kunreuther: 143). Reflections on Community Organization: Enduring Themes & Critical Issues, edited by Jack Rothman, contains a wealth of articles by academics interested in community organization. A Citizen’s Guide to Grassroots Campaigns, by Jan Barry, addresses a range of relevant topics to grassroots engagement organizing. A chapter on “Grassroots-to-Global Civic Action” may provide historical context for organizations today addressing global foreign diplomacy issues that impact local communities (Barry: 92). Robert Fisher’s Let the People Decide: Neighborhood Organizing in America traces community-based movements in the U.S. from the late 1800s through the 1980s, providing further historical context.

There is a wealth of articles dedicated to the field of CBO organizing. A few stand out. “Community Empowerment Strategies: The Limits and Potential of Community Organizing in Urban Neighborhoods,” Peter Dreier. “Approaches to Community Intervention,” Jack Rothman. “Legitimacy, Strategy, and Resources in the Survival of Community-Based Organizations,” by Edward T. Walker and John D. McCarthy. “Reframing Community Practice For the 21st Century: Multiple Traditions, Multiple Challenges,” William Sites, Robert J. Chaskin and Virginia Parks. Robert Sampson’s “What ‘Community’ Supplies,” is a detailed review of literature.

Faith-based Organizing Literature

A more detailed review of the growing body of literature dedicated to faith-based organizing is beyond the scope of this work. Faith in Action: Religion, Race, and Democratic Organizing in America, by Richard L. Wood, provides comparison between the faith-based PICO and racial justice analysis-based CTWO national networks. Organizing Urban America: Secular and Faith-based Progressive Movements, by Heidi J. Swarts is also useful. Several other academic articles are included in the bibliography accompanying this article.

Social Movements Literature Review

It is unfortunate that all too often, academic literature creates separation between Social Movements theory and grassroots CBO organizing. Such mutual exclusivity permeates public perceptions regarding the reflexive interplay of community organizing and broader movements for social and economic change. What this article intends to do is to reveal, through a discussion of CBO and Occupy interplay, is a symbiosis of the two. Those who have participated in prior community, labor and policy change efforts were proven instrumental in the formation of Occupy, alongside activists with other long-standing progressive change efforts. Likewise, the Occupy movement awakened and trained countless new organizers and activists, many of whom joined established community, labor and even electoral efforts post-Occupy. Nonetheless, grassroots organizers and social movement-minded organizers and activists alike have been inspired by Social Movements literature, a topical examination of which will follow here.

Community organizers, volunteer leaders and cause-based activists have found inspiration in academic examinations of historic movements such as the Womens’ Suffrage movement, Feminist movements, the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, in Marxist (including post-Marxist, Maoist, Anarchist, Socialist, and Communist) and Populist movements, in Liberation Theology, and the Colonialist and Post colonialist movements, to name a few (Antonio: 33). Many organizers and activists have incorporated political and popular education about previous social movements among their leadership base, connecting grassroots leaders within a larger history and worldview of social action.

Bill Moyer, in Doing Democracy: The MAP Model for Organizing Social Movements writes that: “Social Movements are collected actions in which the population is alerted, educated, and mobilized, sometimes over years and decades, to challenge the power holders and the whole society to redress social problems and grievances and restore critical values.” That is not so far removed from the classic community organizing strategy of issue identification, research, education, mobilization, action and reflection. Moyer writes: “Social movements promote participatory democracy. They raise expectations that people can and should be involved in the decision-making process in all aspects of public life,” primary tenants of bottom-up grassroots CBO leadership models (Moyer, et. al.: 10).

Readers interested in a further rooting in Social Movements Theory may find inspiration in the following works. One is This Could Be the Start of Something Big: How Social Movements for Regional Equity are Reshaping Metropolitan America, by Manuel Pastor Jr., Chris Benner, and Martha Matsuoka. A Primer on Social Movements, by David A. Snow and Sarah A. Soule is another. Social Movements: Critiques, Concepts, Case-Studies, edited by Stanford M. Lyman, allows multiple authors to contextualize broadly on social movements and collective action. Frontiers in Social Movement Theory, edited by Aldon D. Morris and Carol McClurg Mueller connects social movements theory to broader dominant theories found within the field of academic Sociology. Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements: Political Opportunities, Mobilizing Structures, and Cultural Framings, edited by Doug McAdam, John D. McCarthy and Mayer N. Zald, provides a more international focus in exploring social movement processes. David S. Meyer focuses on the ins and outs of social movement strategies and tactics of protest, mobilized dissent and direct action civil disobedience in The Politics of Protest: Social Movements in America.

Occupy Movement Literature Review

The strongest debates over the role and impact of the Occupy Wall Street 99% Movement came from online public debates on mainstream sites such as Twitter, Facebook and Reddit and on web platforms such as occupywallst.org, occupywallstreet.net, occupytogether.org, occupyvideos.org, interoccupy.net and occupii.org, to name a few. Live streaming technology allowed viewers across the globe to keep up to date on worldwide occupy activities in real time and video sites such as youtube.com allowed wide dissemination of occupy public demonstrations and exposed the world to police repression of occupiers at campsites. Free book share libraries also sprung up at campsites, evidence of the movement’s dedication to political and popular education combined with tactics. A body of literature has also emerged documenting aspects and ideologies accompanying the movement.

Noam Chomsky, a respected voice among many occupiers, published Occupy from the “Occupied Media Pamphlet Series” (http://www.zuccottiparkpress.com), a published response to Occupier questions upon a visit to Zuccotti Park. In Occupy the Economy: Challenging Capitalism, Richard Wolff facilitates a conversation with journalist and writer David Barsamian that reflects on the Occupy movement’s formation in response to the U.S. economic crisis. Sarah van Gelder and Yes! Magazine’s edited This Changes Everything: Occupy Wall Street and the 99% Movement, early released, provided a how-to guide for many would-be occupiers. Occupying Wall Street : The Inside Story of an Action that Changed America was also released early on. Its writers are anonymously and collectively listed as “Writers for the 99%.” Occupy Nation: The Roots, The Spirit, and The Promise of Occupy Wall Street, by Todd Gitlin, addresses issues such as the “Splendors and Miseries of Structurelessness” and “Co-optation Phobia” (issues raised by many occupiers interviewed in this work) and “Can the Outer Movement Get Mobilized?”—a theme relevant to this study’s inquiry into the relationship between the street-level activities of Occupy and the efforts of established organizations to capitalize on the momentum of Occupy and work toward campaign victories and structural systems change. To quote: “If Occupy’s inner movement is otherwise occupied, unlikely to coordinate on a political strategy in the foreseeable future, what of the outer movement—the trade unions, liberal lobbies, and professional groups, the Congressional progressives, all the membership and Washington-centered organizations that specialize in federating, horse-trading, infighting, and at times getting practical things done?” (Gitlin: 206). The Uprising: An Unauthorized Tour of the Populist Revolt Scaring Wall Street and Washington, by David Sirota, provides context for the ways in which resistance was already brewing in the years leading up to the formalization of the Occupy movement.

Online Social Media Advocacy Literature Review

Jessica Clark and Tracy Van Slyke’s Beyond the Echo Chamber: Reshaping Politics Through Networked Progressive Media., reveals how previously unheard progressive journalists found voice and formed organized community through online blogging, websites and journalism, shifting the public debate away from corporate-owned mainstream media and toward a more progressive conversation.

Anthony Loewenstein’s The Blogging Revolution provides another interesting take on grassroots resident journalism in the internet age. Netroots Rising: How a Citizen Army of Bloggers and Online Activists is Changing American Politics by Lowell Feld and Nate Wilcox and David D. Perlmutter’s Blog Wars, though focused on online media as its own end, should prove useful for on-the-ground organizers.

Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age by Manuel Castells chronicles recently emerged revolutionary and protest movements across the globe, from Tunisia to Iceland, Egypt and the Arab Spring. Castells' exposition confirms sentiments expressed by many who recognized that movements such as the large scale immigrant rights protests of 2006 or the uprising in Iran, though aided by Myspace, Twitter and Facebook, were nonetheless the product of years of real life relationship building among a diversity of core leadership teams. Taking on the System: Rules for Radical Change in a Digital Era by online progressive force Daily Kos founder Markos Moulitsas Zuniga is a step-by-step guide for mobilizing online action.

Advocacy, Activism, and the Internet: Community Organization and Social Policy, edited by Steven F. Hick and John G. McNutt raises the voices of numerous writers dedicated to promoting and reinvigorating traditional issue-based organizing practice. Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Activism by Paolo Gerbaudo and Share This!: How You Will Change the World with Social Networking by Deanna Zandt may serve as similarly pragmatic resources for the increasingly net-savvy CBO and social and economic justice field.

Clay Shirky’s Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations reveals how everyday citizens and residents, unconnected with pre-existing organizations, have used the internet to mobilize a quick-to-action base around very localized, sometimes even individualized personal struggles. Many organizers interviewed for this study argued that such immediate change remains isolated and “silo’d” if not connected to sustainable organizations with a committed ongoing base. Yet the emergence of Social Media technology at every laptop, desktop and tablet’s fingertips has provided a groundswell of new, diverse and potentially far-reaching short-term victories and long-term fights.

A further listing of online tools for Organizers and tools for online Social Media organizers is included at the conclusion of this article under Appendix A.

Methodology

For this study, I interviewed practitioners in the fields of CBO organizing, online Social Media and Occupy to get their perceptions and perspectives on the influence each respective entity has had on the other. This reflexive mutual relationship of the three will attempt to address opportunities and challenges inherent to the process of seeking broader, collaborative-based organizing on the contemporary Left. Gaining perspective from practitioners will have a profound effect on stimulating discussion in the field about new opportunities and challenges toward building broad-based cohesion: what has gone well, what hasn’t and how to better anticipate seizing future moments of transformative possibility.

This article focuses on a case study of the organization SOUL (Southsiders Organized and United for Liberation), based in the Woodlawn Neighborhood in Chicago, and their collaborative efforts with city-wide coalitions such as the Grassroots Education Movement (G.E.M.), The Chicago-based city-wide Grassroots Collaborative; with regional and statewide-based organization IIRON and the national organizing network National People’s Action (NPA). The work of S.O.U.L. is analyzed in making a case for local to global collaborative strategies. A gap in theory that addresses coalition-building and collaborative organizing strategies within existing Community Organizing and Social Movements scholarship is a major impetus for writing this article. Finally, opportunities and challenges to developing a global focus to domestic U.S. progressive organizing, to counter the negative impact in local and global communities that is the result of the last 40 years of increasingly globalized corporations and capital is addressed. This study makes an argument for where organizations, through a focus on corporate accountability among increasingly global corporations, are already adopting a global focus.

This study provides several case study examples of organizations, coalitions and networks that are transforming their approach to the work they do, influenced by the advent of online Social Media and the Occupy movement.

Methodological Grounding in SOUL, IIRON and NPA

In the course of working with SOUL as primary case study, the author performed campaign-based corporate and legislator accountability research for the organization. In addition, the author conducted nine months of field work, acting as an activist participant observer on behalf of a diversity of SOUL-related campaign efforts, to learn more about the organization’s unique approach connecting local campaign work to broader systemic change efforts. SOUL is working in collaboration with several other Chicago and Illinois-based community organizations, Occupy Chicago, and across the country on national campaigns through National People’s Action. Honing in on SOUL’s model of community-based organizing will present a model of local to global organizing capacity I will then connect to challenges and barriers to engagement with Occupy-like Social Movements and online Social Media advocacy.

I make the NPA model of local to national campaign organizing, as well as its more recent adoption of online Social Media techniques, coupled with my work with SOUL and their work with IIRON, the central foci of my research. NPA affiliate organizations have also worked collaboratively with Occupy groups on like-minded campaigns, subverting the sometimes notion that Occupy has been a group that, although professing to represent the issues of the 99%, instead manifested itself as a collective suspicious of the actions and intent of more established social justice non-profits, thus limiting broader attempts at deeper collaboration. Honing in on case example coupled with additional in-depth interviews will help make the larger argument that real social movement-based change is more possible when established, funded organizations and loosely affiliated, largely unfunded forming Social Movements groups such as Occupy join forces in further pursuit of a truer 99% movement.

TABLE 1 provides a breakdown of participating interview respondents. Vertical column 1 illustrates the professional and volunteer participation among respondents, revealing that many who became involved in the Occupy movement possessed prior experience in community organizing efforts. The presence of organizers with experience in both CBO and Occupy reveal a reflexive relationship among CBO and Social Movements participants that is contrary to public and academic assertions that community organizing and social movements comprise distinct and separate space. Those whose primary participation is in online Social Media advocacy are designated with an “X.” Respondents with online advocacy as a component of their participatory duties are designated with an “O” while others who participate in online advocacy in one form or another are denoted by a “—.”

TABLE 1: Interview Respondents Organizing/Activist Experience|

Interviewee Experience |

CBO-Local |

CBO-National |

Occupy |

Social Media |

Labor |

Campus Organizer |

|

Com Org |

X |

X |

|

O |

|

|

|

Com Org |

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Com Org |

X |

X |

|

-- |

|

|

|

Com Org |

X |

X |

|

-- |

|

|

|

Com Org |

X |

|

X |

-- |

|

|

|

Com Org |

X |

|

|

O |

|

X |

|

Com Org |

X |

|

|

-- |

X |

|

|

Com Org/Occupy |

X |

|

X |

O |

|

|

|

Com Org/Occupy |

|

X |

X |

X |

|

|

|

Com Org/Occupy |

X |

|

X |

O |

|

|

|

Com Org/Occupy |

X |

|

X |

-- |

X |

|

|

Com Org/Occupy |

X |

X |

X |

-- |

|

|

|

Occupy |

|

|

X |

-- |

X |

|

|

Occupy |

X |

|

X |

-- |

X |

|

|

Occupy |

|

|

X |

-- |

|

|

|

Social Media |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

Social Media |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

Social Media |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

Social Media |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

Social Media |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

CBOs, Occupy and a “Positive, Pragmatic Diversity of Tactics”

The Occupy movement brought to light the ideology of a “diversity of tactics.” However, I argue that the movement was hindered by the fact that, among a faction of those involved, diversity of tactics came to mean tactics of provoking conflict with police and leaving some members to engage in violence and/or property damage, thus distancing the issues others were attempting to bring to the forefront of the U.S. debate. The conversation regarding diversity of tactics including violent provocation must be addressed inclusive of discussions about police brutality in regard to peaceful Occupy civil disobedience resisters, a nationally coordinated FBI crackdown on camp sites, taxpayer funded FBI and NSA surveillance of participants, and encroachment upon the 1st Amendment rights of individuals to participate in civil disobedience.

I posit the notion of a “positive, pragmatic diversity of tactics” which departs from the tactics adopted by some Occupy groups and that discounts violent approaches to highlighting issues of social inequality, stratification and injustice, as methods incapable of achieving the broad mainstream public support needed to implement issue-based ideologies or achieve legislative, electoral, corporate culture and broader societal change. Instead, I argue that a positive, pragmatic diversity of tactics has already been evident—and can grow in the future—through effective collaborations between online Social Media activists and on-the-ground social justice organizers and activists, and between unfunded Occupy and Occupy-like groups and established, funded CBO social justice organizations.

Online Social Media Impact Focus

An effective blend of traditional approaches with innovative technological online interaction, enacted across organizational styles and approaches, represents an exciting new medium worthy of academic attention. The emergence of micro-blogs and other online platforms means an organization or advocacy group can develop web-based content with little to no cost to operate. A host of new sites offer virtually anyone with web access the chance to spread awareness of their issue across continents through sites such as Care2, Convio, Salsalabs.com, Change.org, to name a few. And the growth in popularity of social networking sites--from early Friendster to Myspace to Facebook, Twitter, Google+, Tumblr, Reddit and hundreds of other sites—allow the sharing of advocacy information across multiple platforms.

Burgess and The Chicago School of Sociology’s Concentric Circles Applied to CBO and Collaborative Organizing Strategies

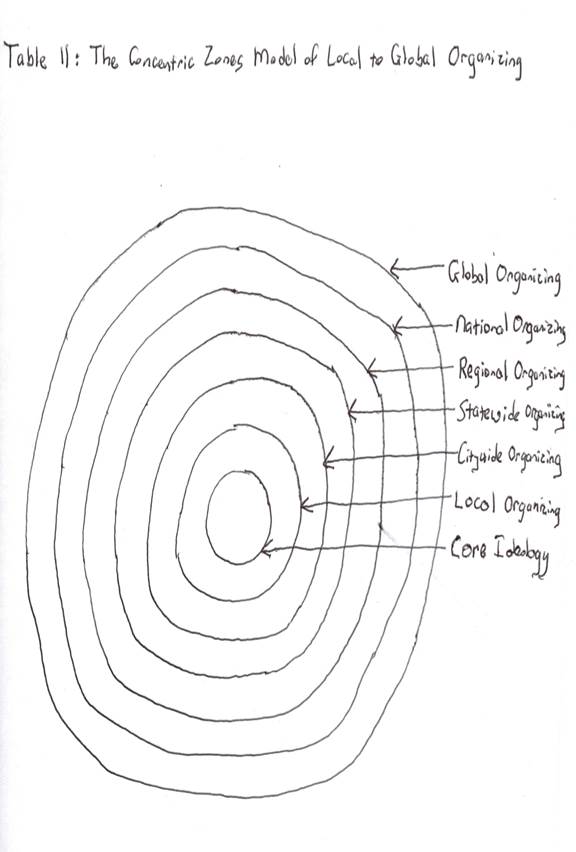

Ernest Burgess is credited as one of the founding theoreticians ushering in the now internationally recognized Chicago School of Sociology at the University of Chicago. The Chicago School that emerged in the early 20th Century believed that Sociology students should get out of the classroom and into the field, turning the study of social groups into real-world laboratories. Burgess is best known for his “Concentric Zone Model,” which provided a template for the formation of urban cities, from their concentric city center industrial core to mixed residential and commercial zones to the outlying inner and outer suburbs. For this article, I take Burgess’ conception of concentric circles as analogy for the ways in which CBOs are forming organizations capable of working locally and, ultimately, globally. The model I present starts with the organization’s ideological core, then moves outward, from local, city wide, state wide, regional, national and global concentric circles.

Faith-based Organizing and Organizational Core Ideology

SOUL, formed in 2006, is a coalition of 24 congregations that stretch from the south side of Chicago to the south suburbs. The organization is currently developing a leadership base that stretches beyond the church sphere. As one inter-faith Organizer once told me: “All religions contain a component of belief in social justice.” The role of the organizer is to tap into that core social justice belief in order to motivate first pastors, then lay leaders, to get involved with the process of identifying root cause social justice issues and to embrace the belief that social change is possible when diverse churches recognize their common social justice impulse and put it to action through joining a faith-based community organization.

The majority of S.O.U.L.’s member churches are historically black, predominantly Christian churches. However, successful models of faith-based organizing have emerged in community geographic areas where churches, cathedrals, mosques, synagogues and temples are joining institutionally based multi-faith organizing efforts. A number of national organizing networks have developed organizing models that perform outreach to churches, social service agencies and other community institutions. Some espouse a specific faith-based ethic. Others are not predicated upon a model of joining institutional members, preferring instead door-to-door outreach in neighborhoods with the hope of engaging and building leadership among populations not already empowered through their membership in a church. Other national networks have adopted a core racial justice, transformative or global perspective as their core ideology. I argue that all organizations have certain core ideologies that guide their work, implicit or explicit. Such ideology would comprise their inner core concentric circle.

Local Organizing

Regardless of the methods or ideology enacted, most organizations recognize that early on in the organization’s growth, sustaining an active, mobilized base requires winning incremental victories that allow leaders to see positive results in their efforts. These smaller issue campaigns are commonly referred to as “stop sign” issues. In the case of SOUL, the organization has structured itself such that many of its institutional member churches have their own local social justice councils, dedicated to local issues even as the organization addresses a broader geographic focus. To provide one local campaign example, SOUL has undertaken an ongoing campaign for a local Arts and Recreation Center in the Bronzeville neighborhood, having identified a shortage of City field houses on the south side.

The recent addition of new SOUL institutional member the Bridgeport Alliance adds further diversity to SOUL’s model of organizing through the inclusion of a non-church based group. The Bridgeport Alliance has been SOUL’s first entre into education organizing, as three Bridgeport area neighborhood schools were facing closure. The organization did it’s own research and was able to convince CPS that the metric being used to determine which schools to close wrongly identified its schools as being underutilized. Additional SOUL institutional members working on local campaigns include the Coalition for Equitable Community Development, HP Cares—Hyde Park and Benton House—Bridgeport. Returning to the concentric circles model, local organizing—only a few examples of which are addressed here—comprises an organization’s second concentric circle.

Citywide Organizing

SOUL has joined citywide coalitions focused toward achieving citywide policy change, such as the Grassroots Education Movement (GEM), a coalition comprised of grassroots education reform CBOs and allies throughout the City. The group formed in response to a City announcement to close 50 of Chicago’s 600 public schools. The group has also formed to preserve public education.

SOUL is also a member of the Grassroots Collaborative, a coalition of 11 Illinois CBOs and labor unions working together to achieve common goals. Mostly centered in Chicago but with some statewide presence, the Grassroots Collaborative bridges the gap between the third concentric circle of citywide work and the fourth surrounding circle seeking impact on a statewide level. The Collaborative first formed in 1998 and, working in collaboration with additional Chicago-based grassroots organizations and unions, successfully pushed passage of a Living Wage ordinance for City contracted employees in Chicago. Subsequent organizing efforts resulted in a successful campaign to index minimum wage increases to a cost of living adjustment (http://www.thegrassrootscollaborative.org).

Community-Collegiate Organizing

SOUL’s model of organizing possesses a unique additional component, the institutional membership of the Southside Solidarity Network (SSN). SSN is a University of Chicago-based Registered Student Organization (RSO). This addition provides a unique layer beyond SOUL’s congregation-based membership. The presence of SSN ensures that younger organizers have a say in advancing the larger organization’s agenda. SSN’s student activists also help bridge the historic divide between the affluent campus and economically under resourced surrounding communities. SSN is currently working in collaboration on a campaign to bring a trauma center to the University of Chicago Medical Center. SSN and SOUL are also members of the regional Midwest organization IIRON and the IIRON Student Network, a coalition of SSN-like campus activist organizations at 6 Chicago-area campuses. Membership in the IIRON Student Network allows SSN to operate according to a multiple concentric circle model as well, addressing campus, surrounding neighborhood and citywide campaigns through participation with IIRON, working for change at the state level. SSN participates nationally by sending a contingent to NPA’s annual national conference in Washington D.C. SSN also works on global and environmental issues such as the Divest from Fossil Fuels campaign and exemplifies a local to global organizing model.

Statewide Organizing

SOUL’s first entre into statewide legislative organizing started with a locally identified need. Leaders recognized that large numbers of area housing stock were in disrepair, with outdated boilers and inadequate insulation and air leakages, resulting in high and wasteful energy bills and increased greenhouse gas emissions. SOUL leaders identified that an increased investment in weatherization and modernization would help create jobs on the south side, where unemployment rates far exceed the City average. SOUL spearheaded a program called the Urban Weatherization Initiative in 2009 and took their idea to state legislators. The campaign resulted in the Illinois State Legislature passing the UWI and earmarking $425 million dollars in statewide green jobs. SOUL estimates the initiative will create 20,000-40,000 jobs over a six year period.

SOUL has set its sights on its next statewide organizing campaign—a drive to push state legislators to pass legislation to cut off corporate tax loopholes for Illinois’ largest corporations. The central argument that S.O.U.L. and its campaign allies are making that current state budget problems, including pension reform, education, health care and services to vulnerable low-income Illinoisans would not have to face cuts if the state of Illinois would simply insist that large corporations based in the state pay their fair share in taxes by closing off current loopholes.

SOUL has joined forces with IIRON, a growing regional coalition that began citywide and includes SOUL, Northside POWER and Lakeview Action Coalition (LAC) on the north side of Chicago and the downstate organization Illinois People’s Action (IPA). Other statewide organizations and labor are also joining the fight, which will allow the campaign to leverage state lawmakers on a wider scale. The aforementioned statewide organizing efforts provide examples of the fourth concentric circle of collaborative organizing.

Regional Organizing

The IIRON coalition, newly formed, is a growing regional coalition with national aspirations dedicated to working on campaigns that address corporate accountability. In addition to the aforementioned organizations, IIRON has recently added the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless, IIRON-Will County, the Northwest Indiana Federation of Interfaith Organizations and Green Nation in Detroit, Michigan as institutional members. IIRON, like SOUL, is also a member of NPA.

IIRON’s corporate accountability focus has led to the development of a platform that calls on banks to reduce underwater mortgages to their current appraised value and reduce interest rates to 3%. Banks are called on to allow the repayment of student loan principal without interest and to impose caps on tuition. Pay Day lenders should cap interest rates at 36% and big banks should allow a 2-year period through which consumer debt can be paid back without interest. IIRON seeks Congressional action to reinstate the Glass-Steagall Act and “impose caps on interest rates and bank fees and strengthen the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection.” IIRON also calls for an end to corporate welfare, including an end to Wall Street bailouts, to subsidies of fossil fuels, to the private prison industry and military contractors. The coalition also seeks legislation allowing for the seizure by eminent domain of bank-owned properties that have been vacant for more than 9 months. IIRON has joined the fight to end corporate personhood status and supports total public financing of elections.

Beyond its primary corporate accountability focus, IIRON coalition members are also working to advocate for a $1.2 trillion 5-year investment to create 5.52 million jobs nationally. Taking SOUL.’s statewide green jobs initiative national, IIRON seeks the implementation of a green infrastructure in transit and rail, an increased investment in renewable energy, an end to fossil fuel subsidies and the establishment of a carbon tax. The coalition is pushing for a progressive income tax system, including a 90% top tax bracket for the wealthiest 1%. The group also proposes a Medicare For All health care system, preserving Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid without benefit or eligibility reductions and supports the Employee Free Choice Act. IIRON is also advocating for a reinvestment in K-12 public education (http://www.iiron.org/what-we-believe/). The reason that IIRON as a coalition umbrella can construct such a platform is that its coalition members are working on these issues at the local, city and state level. IIRON has the ultimate goal of growing into a national coalition of corporate accountability minded organizations. In its current manifestation as a regional, 3-state coalition, IIRON comprises the fifth surrounding concentric circle.

National Organizing

NPA, based in Chicago for 40 years, is a national network of community organizations like SOUL and IIRON, which claims 26 organizations in 14 states, from California to Maine. Scholars and policy experts have credited NPA (formerly NPA/The National Training and Information Center (NTIC)), as the grassroots organization responsible for passage of the Community Reinvestment Act in 1977, resulting in over $4 trillion dollars of bank reinvestment in low-income communities. However, since the CRA’s passage, banks have lobbied relentlessly to weaken the regulatory provisions of CRA as well as the concurrent NPA victory, the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA). Further, the more recent phenomenon of Predatory Lending has promptd NPA and other networks nationally to continue to organize to preserve the original intent of the CRA.

The NPA network’s corporate banking accountability focus has relentlessly targeted big banks, their subsidiaries, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, as well as the three main government bank regulation agencies, and reveals how mortgage lenders continue to attempt to dodge CRA requirements. In response to the financial collapse of 2008, NPA formed the MakeWallStreetPay.com campaign, in order to advance a progressive agenda that refutes austerity initiatives and calls for banks to be held accountable for their role in the ongoing mortgage crisis.

NPA is working nationally as the IIRON network is working statewide to ensure that major corporations pay their fair share, that legislators work to close corporate tax loopholes and mega-corporations reinvest over a trillion dollars currently held in offshore accounts. A self-professed “power-based” organization, the NPA network’s dedication to targeting the unjust policies of the major banks, most of which are global in scope, does comprise “transformative” organizing. The kind of local to national organizing model that NPA embodies comprises the sixth concentric circle of collaborative organizing potential.

Local and National Community-Labor Alliances

Labor-Neighbor coalitions between unions and community organizations have become increasingly popular over the last fifteen years or more, as progressive unions have recognized that their members don’t just encounter injustice at the workplace but in the communities in which they live as well, particularly as those unions have worked to expand beyond their traditional membership base to organize lower wage workers. Community organizations have similarly recognized that the community members that comprise their leadership base face obstacles at work and that community support of worker organizing efforts, support for local living wage ordinances and advocacy for right to organize legislation impact their leaders. National “Labor-Neighbor” collaborations, though still nascent, provide indication of the positive benefit of strength in numbers in forming a more cohesive, unified progressive Left. Some collaborative efforts are short-term and address immediate organizing campaign needs. Others are designed to be more formal ongoing campaigns.

In addition to labor-neighbor coalitions, NPA as a national CBO network has teamed up with two national unions on like-minded campaigns that culminated in joint mass protests in Washington D.C. In 2010, following the 2009 financial crash, NPA joined forces with the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and the national labor-neighbor organization Jobs With Justice (JWJ). The coalition shut down a convening of the American Banker’s Association (ABA).

The coalition also protested the estimated $143 billion in bonuses top bank executives gave themselves for their role in the economic meltdown, effectively pushing the issue into the national mainstream debate about what the regulatory response to the bank-induced financial crisis should be. Increased pressure placed on Bank of America and a direct action nonviolent protest at the home of B of A’s CEO resulted in the bank announcing a freeze on foreclosures in all 50 states, as the coalition further pushed for a nationwide moratorium on foreclosures. The California-based PICO national network and the Chicago-based Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE) and the Northwest Federation of Community Organizations (NFCO) joined that campaign as well, an early indication of the potential for more broad-based collaboration across national networks (http://npa-us.org/category/tags/seiu).

Starting in 2012 and continuing in 2013, NPA teamed up with National Nurses United (NNU), as well as Health GAP, Vocal-NY and ACT UP and formed a campaign coalition and organized a 2,000 strong march in D.C. during the International AIDS Conference. The AIDS crisis and a broader agenda were addressed. According to NNU’s website: “dressed in the colorful hats and garb of Robin Hood, we posted a declaration of Robin Hood Tax principles at several locations: the offices of the Securities Industries Financial Management Association, Bank of America’s D.C. offices and at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce national headquarters.” The coalition believes that “a small sales tax on trading in stocks, bonds, derivatives and currencies could raise $350 billion a year in the U.S. alone” (http://www.nationalnursesunited.org/blog/entry/robin-hood-answers-call-for-aids-funding).

In April of 2013, NPA and NNU again joined forces, and new allies joined the fight, including Friends of the Earth, the international union Public Services International and the national Amalgamated Transit Union. Continuing the Robin Hood theme, protesters joined forces to call on President Obama and Treasury Secretary Jack Lew to support H.R. 1579, the “Robin Hood Tax” financial transaction tax on Wall Street. (http://www.nationalnursesunited.org/press/entry/thousands-in-robin-hood-hats-to-demand-president-obama-secretary-lew-suppor ).

Any organizer who does collaborative work knows that the process is difficult, even as participants see the potential collective power in forming coalitions. The increased strength in numbers, however, can’t be downplayed and collaborations such as these are revealing the potential benefits of broader collaboration. For purposes of the concentric circles model, we will term national labor-neighbor collaboration the 6.5 level concentric circle.

Community Organizing-Social Movements Collaboration

CBO organizing is a part of ongoing Social Movements efforts, although academics and organizers often treat the two as mutually exclusive. The emergence of the Occupy Wall Street 99% Movement provided an unprecedented opportunity for a convergence of these disparate entities. The emergence of Occupy pushed CBOs and unions to seize this historic moment, and droves of community and union organizers, volunteer leaders and rank and file members hit the streets in support of Occupy, actively participating at campsites, in street protests and media events. Although some were mistrustful, many Occupy enthusiasts saw the value of joining forces and remained true to the principle that, to build a representative 99%, relationships needed to be formed across diverse constituencies. At its best moments, the Occupy Movement presented progressives with a glimmering vision of what a truly inclusive, broad-based movement could look like.

In Des Moines, Iowa, several staff of the NPA affiliate Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement (Iowa CCI) were arrested when police came to forcibly remove the camp site they had constructed in People’s Park, which faced the State Capitol Building. That act of early solidarity foreshadowed the growth of an Occupy Iowa movement that spread to over 10 cities and towns across the state where anti-war activists, disgruntled everyday residents, and established organizations like Iowa CCI worked in constant and ongoing Occupy collaboration. It was in some ways a natural fit as Iowa CCI who, as member of the NPA network, had been organizing against banking institutions for decades and found common purpose with occupiers frustrated with the big banks’ role in the 2008 financial collapse.

Occupy’s national days of action and ongoing push to convince U.S. bank consumers to close their accounts with the nation’s largest banking institutions not only led to millions of people leaving the big banks. It also created a climate that put banks on the defensive and enhanced CBOs’ ability to hold them accountable. Just as Occupy appeared to be losing some of its steam through the winter months and repeated, often coordinated police crackdowns, the NPA-initiated “99% Spring” emerged. In Des Moines, Iowa CCI leaders, labor activists and Occupy participants from across the state convened for a day of speakers, trainings and break-out discussion sessions that culminated in a 500-person nonviolent direct action at the home of the president of Wells Fargo Home Mortgage. Nationwide, over 200 organizations officially endorsed the 99% Spring and thousands of new leaders were trained in states across the country (http://npa-us.org/99-spring-full-bloom).

In Chicago, a similar spirit of broad-based collaboration materialized. Less than a month into the emergence of Occupy, The Chicago Federation of Labor joined with Occupy, NPA and its affiliate organizations and a diverse array of organizations and activists across the city in a week of actions that saw five separate marches throughout the city convene downtown. An estimated 7,000 people attended the marches, focused on housing, education and job creation. NPA activists donned their Robin Hood costumes for the first time and took to canoes on the Chicago River. The convergence actions were designed to also call attention to the Mortgage Banker’s Association Annual Convention and Expo and the Futures and Options Expo, taking place in Chicago the same week. Both the Iowa and Chicago examples are but two among countless examples nationwide and across the globe of greater collaboration among Occupy, CBOs and labor.

Global Organizing Potential

Anti-war protests when the Bush Administration invaded Iraq quickly spread global. But they failed to stop the war. Nonetheless, continued dissent on the Left eventually turned the tide and eroded the credibility of the oil seeking war machine. The Occupy Movement likewise quickly spread global yet, in its relatively short lifespan, failed to achieve the broad, transformative political change participants were seeking. Nonetheless, the movement has had a reverberating effect. Millions of U.S. bank consumers left major banking institutions. To date, 16 states have passed legislation seeking to overturn Citizens United.

In the long run, can the unprecedented global, like-minded action that Occupy represented serve as a larger wake up call to U.S. and global community and labor organizing? To do so, CBOs will have to look beyond their immediate competition over foundation funding and unions are going to have to progress beyond their recent history of protectionist stances. The possibilities are there. Income inequality in the U.S. and globe has reached a tipping point that is unprecedented in world history. Global organizing is the 7th concentric circle.

Online Social Media Advocacy as a Tool of Broader Participatory Potential

The emergence of web-based technology was originally touted as an opportunity to globalize and democratize media and revolutionize the information age. Yet the basic tenants of free market capitalism quickly found their way onto the web. The digital divide persists. Still, the advent of online Social Media advocacy has become a tool that social, economic and environmental justice organizations have largely embraced as an opportunity to bring a new web-savvy population into the activist and organizing fold. There has been concern that the most salient methods of online advocacy, namely petition signing and donation solicitations, have had a dual effect of pacifying a new generation of potential advocates.

For CBOs and Occupy-liked social movement efforts, organizers and activists have acknowledged a need to use online advocacy as a means of encouraging potential participants to get involved in real-world face-to-face campaign work. Email, list-serves and social networking have proven valuable in keeping leadership informed of public events, campaign development and direct action protests.

Globalization and the Grassroots Triple Convergence

In his book on new computer technology and Globalization, The World is Flat, Thomas L. Friedman writes of a “triple convergence” that led to what he calls “Globalization 3.0” (Friedman: 178). Consisting of the “combination of the PC, the microprocessor, the Internet, and fiber optics,” 3.0 resulted in “the creation of a global, Web-enabled playing field that allows for multiple forms of collaboration—the sharing of knowledge and work—in real time, without regard to geography, distance, or, in the near future, even language” (Friedman: 176-178). Friedman argues that, as a result, the world is “flattening” and that entrepreneurial tools of technology are now in the hands of a broader percentage of the world population.

His model, however, presents an image of a world where the digital and economic divide and the accelerating global income inequality of the last fifty years simply cease to exist. Such a promising phenomenon is unlikely to fully permeate the myriad of inequalities faced by low-income communities on the south side of Chicago, where SOUL operates, or in economically depressed areas throughout the globe. Still, the increase of online Social Media access alongside CBO and Occupy-like social movements among an ever more technologically savvy U.S. and world population (what I will term the “grassroots triple convergence”) are combining to turn the political tide ever slowly toward a more egalitarian-seeking society.

In “Globalization, Producer Services and Income Inequality across U.S. Metro Areas,” Terry Clark, Xing Zhong and Saskia Sassen analyze globalization impacts on changes in income inequality” from 1980-1990—pre internet age--and find that “income polarization has risen” (Clark, Zhong, Sassen: 385). “The international flow of labor polarizes earnings by depressing wages among low-income workers.” Furthermore: “Globalization and income inequality have both risen in recent decades,” and: “Income inequalities between the rich and poor in American metro areas seem to be increased by global forces: locations with more global exposure increase the polarization of their earnings distribution” (Clark, Zhong, Sassen: 385-390). It is clear that the rising tide of globalized technology in the context of free market capitalism and ongoing global trade agreements is not lifting all boats.

Kevin McDonald’s Global Movements: Action and Culture, stands out among a growing literature highlighting grassroots everyday people’s movements that are bringing into alignment the three components of the grassroots triple convergence. The Case Against the Global Economy: & For a Turn Toward the Local, edited by Jerry Mander and Edward Goldsmith, provides a good primer for activists seeking to bolster the case for an alternative vision of a more glocal, sustainable world economic future. Another important edited volume, by Mander and John Cavanagh, is Alternatives to Economic Globalization: Another World is Possible. Ben Shephard’s From ACT UP to the WTO: Urban Protest and Community Building in the Era of Globalization may also prove useful for organizers and activists. Finally, William Sites Remaking New York: Primitive Globalization and the Politics of Urban Community reveals the intersections of globalization and community development.

For more egalitarian alternatives to unfettered free market global capitalism and hegemony to be possible, grassroots movements--both local and incremental in scope, as well as far-reaching and transformative—will need to be the catalysts that push those in power to adequately respond to the needs of everyday global residents. Capital has proven its ability to globalize at the push of a button. There has been a lag in grassroots and progressive policy movements to catch up. Yet millions are marching in the streets, aided by online technology, against repressive regimes, against environmentally and humanly reckless mega-corporations. The government-corporate collusion is steadily being exposed and the mainstream populace is slowly waking up, opening up possibilities for an ever-broader popular resistance.

Findings: In the Words of Organizers and Activists

Community-Based Organizing and Occupy: Reflexive Impact

Interviewees were first asked a series of questions designed to tease out their perceptions of the relationship between the Occupy movement and CBO organizing. One Occupy organizer in Des Moines, Iowa described Occupy as her first experience with activism, and was later hired as a community organizer with Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement (Iowa CCI). “Occupy had an impact because people who came about the issues [through Occupy] but weren’t previously involved were able to connect to others. Occupy got more people involved than before in established organizing campaigns.” Another Des Moines-based occupier had his first experience with activism through Occupy and felt the movement had a reflexive impact on CBO efforts. “They [CBOs] took on the words and phrasing of the 99%...and Occupy helped expand awareness of economic discrepancies, while traditional groups helped make the movement more mainstream. The result was more mainstream awareness of activism in general.” According to another CBO organizer interviewed, Occupy aided CBO efforts in general by “emphasizing and re-illustrating the importance of direct action to social change.”

An organizer in Chicago who works with a CBO that has collaborated with Occupy Chicago echoed a common theme. “The biggest impact for community organizations was the narrative shifting of Occupy. And Occupy created room for progressive organizations to get out publicly.” Another long-time Chicago organizer and Occupy participant provided a similar take. “The media that Occupy received helped the organizing movement. Organizing doesn’t reach your average American. Occupy showed a physical presence in the streets.” A New York-based organizer with experience in the labor movement felt the impact of Occupy was “pretty immediate. “The impact in language, how we define the conditions of experience and the struggle had a uniting message. Occupy made it okay to talk about economic conditions, showed that material issues matter. It was not just ideological. There was an excellent class analysis; a shared struggle. Everywhere on the progressive Left, people were getting involved.”

The Chicago-based mass convergence demonstration dubbed “The Showdown in Chicago” proved a solidarity defining moment for CBOs, labor and Occupy. “Some of our people [CBO leaders] and Occupy protesters got arrested,” another Chicago organizer responded, as was the case at the onset of Occupy Des Moines. “[CBOs and unions] made Occupy seem bigger and broader. Traditional CBOs could put some leadership into it but Occupy was going to fizzle out.”

Many interviewed expressed that they knew Occupy had a shelf life. To an organizer with FACE, a Hawaii-based “Alinsky-style organization,” the lesson learned was that “social movements like Occupy will be brief, so you need to get in early and capitalize on the momentum.” FACE and Occupy originally found common ground fighting home mortgage foreclosures and passing an anti-foreclosure ordinance. The Occupy and FACE “interaction was mutually beneficial,” said the organizer.

According to the FACE organizer, one occupier, a long-time activist, was instrumental in motivating Occupy to get involved. Contrary to the non-hierarchical, leaderless, consensus-based decision-making model on which it was predicated, nearly all interviewed about their experiences with Occupy recognized that certain leaders emerged through Occupy. In some instances, interviewees reported that such leaders pushed too hard, leading to divisions in the groups that, coupled with state-ordered police repression and decimation of campsites, led to some Occupy groups’ ultimate demise. The organizer in Hawaii felt that, ultimately: “Occupy there came to invest too much of its time in defending its campsite and the right to occupy public space and got distracted from the issues of corporate influence in politics and bank accountability over the financial crisis that initially propelled Occupy to form.”

Another former occupier, now an online Social Media organizer in Atlanta, saw Occupy as having an impact on traditional CBOs in a different way. “Occupy brought questions about foundations and philanthropy [in traditional CBOs] into question. The only way for many non-profits to function is through foundation budgets. [CBOs] saw a rag-tag group of activists with no real money, directly invested and coming together, giving what they can.” Further: “A lot of people who got involved in Occupy had experience working in organizations that pigeon-holed them. Occupy was a chance to work on multiple issues.” While many local and national CBOs are multi-issue in focus, many interviewed also expressed the sentiment that Occupy challenged CBO networks and unions, specifically, to work harder to connect issues, and the progressive Left, more significantly.

Several organizers interviewed made reference to the Occupy Our Homes movement that emerged from Occupy in cities like Minneapolis, Atlanta and New York. According to one organizer involved in both Occupy and as a CBO professional organizer: “Occupy leaders looking to address the mortgage foreclosure crisis or looking for homes linked up with existing organizations and their leaders who were already working on the issue. Occupy leaders helped reinforce that fight.” They did so by physically occupying foreclosed-on homes, to stall eviction while the CBO sought to stall evictions and seek strategies of allowing people to renegotiate their mortgages. In this instance, the funded resources of existing organizations coupled with a mobilized and invested Occupy base resulted in an important hybrid model that continues to fight to save underwater mortgage holders from eviction today.

As Occupy momentum was waning in early 2012, along came the 99% Spring. Conceived by NPA, over 200 organizations nationwide endorsed the week of training and action. From the beginning of Occupy, there were factions in the movement that spoke out against potential co-optation by established organizations. Nonetheless, organizers and occupiers alike came together to participate in the 99% Spring. 50,000 people were trained in organizing strategies and civil disobedience in person and the same number were trained online. According to one organizer and occupier: “the 99% Spring was a mobilized shot in the arm. It carried over into shareholder actions in the Spring.” Organizations purchased proxy shares and sent volunteer leaders to attend corporate shareholder meetings of Wells Fargo in San Francisco, Bank of America in Atlanta and a GM shareholder meeting in Michigan to express grassroots dissent.

The 99% Spring provided an encouraging example of unprecedented collaboration among local and national organizations on the Left. According to an organizer with Sunflower Community Action in Kansas: “The messages of the 99% resonated with our leadership. Our key leadership got the analysis and for us, Occupy and [our CBO work] was a natural fit. Our people attended Occupy gatherings. As an organization we were able to take the articulations of Occupy but move it into a strategy.” Sunflower was successful in bringing 29 organizations across Kansas to unite around the issue of Voter ID laws and voter suppression. Here, an unprecedented coalition of diverse state-level organizations found unity under the umbrella “I Am Kansas” and the KanVote Campaign. According to the organizer I interviewed: “The shared values vision has driven our agenda. We’re still working to convene the group and KanVote has led to the formation of a Kansas People’s Action coalition.” According to an organizer with the Virginia Organizing Project, at the end of the day, Occupy “showed a shift in energy. People were sick of being kicked around in tough economic times” and, regardless of the outcome, which varied across regions of Virginia: “in some areas, Occupy moved new folks into a campaign. In other areas, folks couldn’t connect camp tactics to campaign tactics. Our model requires public official accountability. In some places Occupy focused on the model and process of organizing but could not move people around a campaign.” Nonetheless, where it worked, Occupy and CBOs came together to accomplish impressive things that should encourage future collaborative action.

The Impact of Online Social Media Strategies

Respondents interviewed varied in their assessment of how effective online presence was for organizations that pride themselves on bottom-up, person to person outreach. The Occupy movement certainly epitomized a group of activists committed to making use of online outreach as a means of encouraging people to get out, camp, and take occupation of and action in the offline sphere. Some organizers interviewed felt that online engagement wasn’t as effective when it came to engaging many of their older members. Others saw an online presence as, quite simply, the way things are moving. To these organizers, adopting an online presence was simply the next means of meeting a potential base where they are at.

According to the organizer in Virginia: “We have been cultivating our capability online, but it’s been slow. For our older staff and leaders, there’s no replacement for the in-person 1-on-1. Phone calls are less effective; email is less effective than that. We’d have 150 people say they planned to attend an event advertised through Facebook, but on the day of, only 10 would show up. But to be respected, by media, by public officials, we have to have that online presence. We have a new online database to do targeted action alerts on specific campaigns. We have a full communication staff and we upload activities immediately. Ways to reach younger folks are as important as reaching out along lines of gender, race and class. We’ve started using text brigades, composed of 10 to 50 interns. We’re still figuring out what works in engaging folks.”

The occupier turned Organizer with Iowa CCI, many of whose members are aging farmers, recognized: “Many of our membership are older and not on social networking sites. But they do email. Email and email-based petitions are more effective. It’s a way to get a message out really fast. If people aren’t responding online, you realize you should change your direction. Petitions get more names and help drive membership. I want the data from it to know I’m working on stuff people care about. And yeah, petitions alone can be pacifying. But when someone signs: 1) we thank them; 2) we let them know more they can do to get involved; 3) we give them something additional to do; 4) and we recruit them to be members. It’s about turning that one action into further actions and getting them more involved.”

According to our Chicago campus-based organizers, online engagement: “makes it easier to make organizing social. We post Facebook status updates to let people know we need emergency support. Some people will respond but for the majority of what we do to get people involved, we still need face-to-face interaction, more personal phone calls. We have a list-serve but we don’t always know who is actually reading that. People don’t take risks based on a Facebook post. People step out of their comfort zone and develop relationships by face-to-face action.” Another long-time Chicago organizer who participated with Occupy agreed. Online organizing has “become a good tool beyond the traditional newsletter or organizing flyer. To have an online presence is a good thing. But it won’t replace face-to-face meetings. For the campaign I’m working on, I use a product that tells me if people are reposting a communication, opening it up or forwarding it on. I need that tool to know if I’m reaching my audience.”

The former occupier turned organizer interviewed from Atlanta currently serves as moderator for a handful of national and local Facebook and Twitter accounts. “With Twitter, not a lot of our members are on it. Some chapters do use it. It’s an important tool to tweet things their members want to see. But really, often our tweets are tailored for interaction with allies, the media or foundations. Often we’ll re-tweet something that one of our allies has asked us to share to help get their work out. So it’s useful in building relationships with allies. In some instances, reporters don’t respond to press releases any more. But they’ll respond to a tweet. It does put the ability in our hands to frame an issue before it hits the press. We have a system to ID people who are sharing or reposting our tweets but we’re not always tapping into it well enough to know how to follow up with these people.”

Another occupier turned Organizer with Iowa CCI had the following to say. “Twitter does allow us to mobilize and report in real time. Newspaper reporters are paying attention. And we build our base through online petitions, reaching out to people in remote locations that aren’t otherwise connected to us geographically. It’s also useful for fundraising and keeping program officers informed. But a sole reliance on social media doesn’t build power by itself.” Our interviewee with Sunflower in Kansas had a different take. “For our campaigns, we can no longer just think about direct action tactics. We have to think about messaging on the front end and create our own story. We don’t wait for media to catch up. When we do actions now, we Livestream—we get so many hits. We use it after our actions as well. We have leaders who tweet live from our actions. It adds one to two days of work to an action but the follow-up and impact is huge.”

Coalition-Building and Collaborative Potential

A coalition of close to 30 organizations has formed in Kansas over the last year. The 99% Spring was an unprecedented collaboration. Sometimes collaborative coalitions emerge because an immediate organizing need is recognized and organizations recognize they don’t have the strength in numbers to impact that issue alone. Other coalitions form with a more lasting, long-term aim in mind. The GEM coalition in Chicago came together around school closings yet has the intention of working on school related issues long term. Coalitions like these are continuing to form nationwide. What this trend embodies long-term is a determination among the new, younger leaders of organizations focused on building broader, better connected and stronger coalitions in the face of old organizational divisions and continued competition over limited foundation support and funding.

One of the most promising, broadest nationwide collaborations has been The New Bottom Line coalition. Now well into its fourth year as a former collaboration, the coalition formed as a cross-network community organizing collaboration in response to the 2008 Financial Crisis. The coalition is composed of PICO, NPA, The Alliance for a Just Society and the Right To The City Network. According to the Washington D.C.-based organizer I interviewed “the network first formed working together around predatory lending issues but, following the financial collapse, morphed into working on the foreclosure crisis.” The coalition is recognized as the grassroots driving force behind “putting the issue of principal reduction back into the mainstream discussion.” Their initial national organizing victory came when all 50 state Attorneys General forced “the five largest mortgage service companies to invest $26 billion in providing principal reduction for underwater mortgages.” According to the organizer: “It didn’t go far enough. There is currently $700 billion in underwater mortgages nationwide. We weren’t willing to settle and will keep fighting. It’s a start and helped re-frame the issue away from blaming homeowners.”

Among predominantly rural states, a new ten state coalition, The Food and Agriculture Justice collaboration is forming. According to the Iowa-based organizer I spoke with: “networking on these issues will make us stronger.” In Iowa, CCI first made connection with the Oakland, California-based Oakland Institute, which works on fighting agricultural land grabs in Africa. CCI soon made the connection that one of the most prominent offenders had ties to Iowa State University. Said the organizer: “This issue showed us that problems people are experiencing in Africa have implications for us here in the states. The OI showed us examples of 160,000 refugees getting kicked off their land in Africa. We’ve dealt with family farmers being bought out by corporate agriculture for years. It allowed us to make the connection between on-the-ground examples of wrong being done both here and Africa.” It is examples such as these, along with the growing global influence of banks and large corporations that are pushing organizations to make global connections on issues that have impact their members in their own back yard.

According to the campus-based Chicago organizer, lessons learned in other countries are speaking to the struggles encountered in the U.S. in terms of building a broader, more widespread social and economic justice movement. “We’re seeing countries in Europe, in Latin, Central and Southern America, turning out 100,000 in the streets. But we don’t see that here. Our organizations building movements need to be more inclusive. The ‘you’re with us you’re against us’ mentality doesn’t work anymore.” An Iowa-based occupier largely agreed: “We need people in the U.S. to become more uncomfortable. We’re too obsessed with pop culture. By and large we have food in the belly. It will take millions of people feeling desperate. Other countries feel the discrepancy between the haves and have-nots. Things are going to have to get worse in the U.S. before we wake up.”

New National Collaborations: Community and Labor

Organizers interviewed spoke to other issues organizations are forming around in the U.S. with global implications. Issues around global banking policy, the actions of global corporations that receive huge tax breaks in the U.S. yet continue to lag behind in creating jobs back home; issues like global agriculture giant Monsanto pushing GMO policies affecting people and the environment in the U.S.’s backyard and throughout the globe. The immigrant rights fight, in a country where 11 million people remain undocumented and deportations are at an all-time high, yet the Right continues to push restrictionism, incarceration, deportation and border fence policy over creating paths to legalization, remains a challenge for progressive organizers. The polarization of issues like immigration reform and the inability of organizations to fully shift the debate and push an alternative narrative, remains but one instance where the Left is struggling in the fight to truly shift the national debate, though legislation is currently pending.

Those interviewed identified points where labor and community continue to struggle to make connections and work effectively together. Said one organizer: “It’s important to build deeper relationships with labor unions. They have power in numbers and are an organized expression of the working class.” The organizer with FACE in Hawaii reported that they have formed strong partnerships with UNITE HERE in that state. Overall, he sees a deeper commitment to labor and community working together. “SEIU reaching out to us locally. We responded without asking anything in return. The field is maturing in that way.”

A New York based organizer spoke about SEIU’s nationwide focus in organizing low-wage workers, stretching beyond its traditional member base. “In New York, they have formed relations with Make the Road, a neighborhood organizing group.” As the fight for $15/hr is gaining momentum in cities across the nation, new potential collaborations with community are becoming both necessary and possible. The aforementioned Labor-CBO collaborations NPA participated in has shown promise. Yet across the board labor and community often fail to connect.

Local to Global Organizing: Promise and Challenge

Most organizers admit that organizations, whether working locally, state-wide or as national networks, are still behind the curve in coming together to form a broader movement for social and economic justice on the Left. Beyond bank, corporate and corporate agriculture conglomerate accountability campaigns, groups will first need to look beyond the history of their own funder and ideological-based divisions, link up where possible with labor, and form a broader unified movement in the United States. Nonetheless, a few examples emerged through the course of these interviews that speak to the potential for broader cross-national collaboration. For Hawaii-based FACE, the organization has made connections with a Pacific Island region of organizations coming together to address the impact of the Transpacific Partnership. FACE is further involved with organizations operating in the Pacific Basin that stretches as far as India. The group has even adopted popular and political education exercises rooted in Coconut Theology, the Pacific Island region’s version of South Central American Liberation Theology.

On the other side of the country, the Virginia Organizing Project is reaching out to two networks. The first is the Central European Organizing Collaborative. The second is the Eastern European Organizing Project. VOP participates in an organizer intern exchange with these two regional European networks. By participating in the Alliance for Appalachia, VOP is also sending organizers down to Central America and is engaged in discussions over how issues like fuel extraction and roof top mining negatively impact local communities. Such trends point to a possible positive future where the institution of community organizing, long maligned for its “your block versus my block,” “your network versus my network” divisions, can have the kind of conversations necessary if global community organizing ever hopes to catch up to the globalization of capital and seek formation of its own “grassroots triple convergence.”